- Home

- Tove Jansson

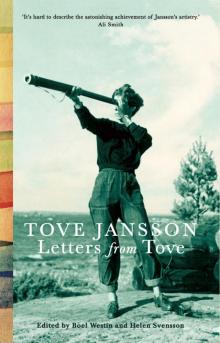

Letters from Tove

Letters from Tove Read online

TOVE JANSSON

Letters from Tove

In the letters she wrote to her family, her dearest confidantes, and her lovers, male and female, Tove Jansson spilled her innermost thoughts, defended her ideals and revealed her heart. To read these letters is both an act of startling intimacy and a rare privilege.

Penned with grace and humour, Letters from Tove offers an almost seamless commentary on Tove Jansson’s life as it unfolds within Helsinki’s bohemian circles and her island home. Spanning fifty years between her art studies in the 1930s and the height of Moomin fame, we share with her the bleakness of war; the hopes for love that were dashed and renewed, and her struggles to establish herself as an artist.

‘A unique and authentic voice that speaks to the reader across time and culture, heart to heart.’

Boyd Tonkin, The Independent

‘Tove Jansson was a genius, a woman of profound wisdom and great artistry.’

Philip Pullman

TOVE JANSSON

Letters from Tove

Edited by

Boel Westin and Helen Svensson

Translated from the Swedish by

Sarah Death

CONTENTS

Title Page

Introduction

“I do so wonder about the future” LETTERS TO THE FAMILY 1932–1933

“I think about you all the time” LETTERS TO THE FAMILY 1938–1939

“I am never alone when I talk to you” LETTERS TO EVA KONIKOFF 1941–1967

“I can see the ideas growing like trees straight through you” LETTERS TO ATOS WIRTANEN 1943–1971

“Under the names of Tofslan and Vifslan” LETTERS TO VIVICA BANDLER 1946–1976

“Do we really appreciate how lucky we are …?” LETTERS TO TUULIKKI PIETILÄ 1956–1968

“Dearest Ham” LETTERS TO SIGNE HAMMARSTEN JANSSON 1959–1967

“A letter that you burn – please! – is better than talking” LETTERS TO MAYA VANNI 1957–1983

“So just conceivably another book” LETTERS TO ÅKE RUNNQUIST 1965–1988

Sources/credits

Index of people

About the Author

Copyright

Tove Jansson in the mid-1950s, in her Helsinki studio.

INTRODUCTION

“THE LETTER” IS THE TITLE OF ONE OF TOVE JANSSON’S EARLY SHORT stories. The last chapter in her 1989 novella Rent spel (Fair Play) has the same title. Both of them centre on the significance of a letter. This was something about which Tove Jansson knew a lot. She was a great correspondent, writing frequently and at length to her family, friends and lovers. Her works teem with letters in a variety of forms, from bobbing messages in bottles to notes and epistolary novels. Letters are written, sent and read in many different places. And lying on the bureau in the Moomin House are Snufkin’s spring letters.

In Letters from Tove we have gathered the letters to those to whom she felt closest, those who were her companions in life, work and love. Our selection is drawn from various extended correspondences that have been preserved. They span six decades, between 1932 and 1988, offering a variety of perspectives on the ways in which Tove Jansson describes her life and work over the years. The first letters are written to her family, her parents Signe Hammarsten Jansson and Viktor Jansson plus her younger brothers, Per Olov and Lars. They were written during Tove Jansson’s time studying in Stockholm and on two extended trips abroad in the 1930s. These are followed by three sequences of letters, all begun in the 1940s: to photographer Eva Konikoff, author Atos Wirtanen and director Vivica Bandler. The long correspondences with graphic artist Tuulikki Pietilä and translator Maya Vanni begin in the 1950s and continue into the following decades. Publisher Åke Runnquist and Tove Jansson start writing to each other in the 1960s and their correspondence extends into the late 1980s. There is also a section of letters from Tove Jansson to her mother Signe Hammarsten Jansson, written after Viktor Jansson’s death in 1958.

All these addressees were of significance to Tove Jansson as a human being, writer and artist, and close to her over an extended period – all her life, in the case of her family, of course. Her letters to them present varying pictures of Tove Jansson the letter writer, depending on whether she is writing as a daughter, lover or friend. Events and individuals can be described in different ways to suit particular recipients, and be seen in different lights. The recipient is often a co-writer, too. But, for Tove Jansson, letter writing is also a way of getting close to others, as in a conversation: “while I am writing, I have you here”, she says in a 1946 letter to Vivica Bandler. Similar phrases crop up elsewhere. “Tuulikki, I am longing to read more of the book that is all about you”, she writes to Tuulikki Pietilä in summer 1956.

Tove Jansson always wrote by hand, never on a typewriter, and her letters are sometimes illustrated, often with pictures of herself in a variety of situations. In her younger days she would write in both pencil and ink, varying her writing paper from occasion to occasion, but later on she usually wrote on unlined white paper in black felt-tipped pen. Writing letters to her closest contacts was a long-felt need for her, but her growing fame drastically altered the conditions of her correspondence. Tove Jansson received an average of two thousand letters a year and she answered almost all of them. This meant that from 1954, when she achieved her major international breakthrough with the Moomin cartoon strip, to the years preceding her death in 2001, she had 92,000 letters to answer. And yet this does not include many of her letter-writing years. “I have lost my enthusiasm for writing letters after all the years of Moomin business, an overwhelming daily task of writing to people I didn’t know and didn’t like,” writes Tove Jansson to her friend Eva Konikoff at Christmas 1961. But there is still a little margin left for “privacy and free will”.

The correspondence reproduced in Letters from Tove falls into the latter category. There is an extensive amount of material, and we have selected 160 of the hundreds of letters after reading through them all. The letters to these recipients were first used in Boel Westin’s 2007 biography Tove Jansson. Ord, bild, liv (English edition, Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words, 2014), in which a number of the quotations and longer extracts are reproduced. But they have not previously been published in an edition with commentaries.

This volume of letters is divided into chapters, one for each addressee, with the letters arranged in chronological order. There is an introduction at the start of each chapter to the addressee and his or her relationship with Tove Jansson. The letters have been reproduced orthographically from Tove Jansson’s writing. This includes punctuation and speech marks. She occasionally misspells names, places and words or uses personal spellings such as “galloppera” (set off at a gallop), but these have been left unchanged. Those dates and the places given in square brackets [ ] are based on postmarks and/or information contained in the letters. In the few cases in which letters have been abbreviated to cut out digressions of a peripheral nature, this is indicated by [ … ]. Some of the letters extend to ten or twelve pages and we wanted to include as many letters as possible to show the breadth of Tove Jansson’s repertoire as a correspondent. The list of ‘Sources’ (p.488) gives details of where the letters are kept. The majority of them are in private ownership, but some are in archives.

The commentaries that precede a number of the letters describe events and circumstances that are crucial to contextual understanding. Tove Jansson sometimes writes letters in swift succession, but sometimes quite a long time elapses between them. Explanatory notes about people and places are to be found at the end of each letter. Individuals normally only appear the first time they are mentioned. In order to keep the commentaries relatively concise, more marginal individuals are omitted. The notes also include some tr

anslations, and clarifications of words and expressions. This applies particularly to Finland-Swedish expressions and “Finlandisms”, but there is also clarification of the language mixing found particularly in the letters written from France and Italy.

In the commentaries, Tove Jansson is abbreviated to ‘TJ’. The diaries and notes referred to in the introductions are to be found in Boel Westin’s biography. The many parallels to Tove Jansson’s literary texts are discussed in several places, but this book’s readers are generally left to see and discover them for themselves.

Tove Jansson’s letters tell us about herself. They encompass descriptions of her life and work, of people and landscapes, and shift between hope and despair, yearning and happiness. They deal with love and friendship, loneliness and solidarity, and also with politics, art, literature and society. But a letter also documents a juncture in time, stops the clock and tells us about things that otherwise get forgotten or sink into the depths of memory. Tove Jansson’s letters describe their period in time through expressions, thoughts and events, and can be read as a blend of biographical and cultural history. They can be literary and lyrical, observant and analytical; they can be cheery, sad, exhilarated, melancholy and sometimes entirely workaday. But they rarely leave us unmoved.

Boel Westin and Helen Svensson

Translator’s note: English words and local place names

Tove Jansson’s letters are written in Swedish but quite often include words or phrases in English; these have been set in italics and their original spelling has been left unchanged. Underlinings have been retained from the original letters.

Local place names appear as written in the letters, for example, FIRENZE rather than FLORENCE. Tove Jansson commonly refers to Helsinki by its old Swedish name of HELSINGFORS (or H:FORS) and abbreviates Stockholm as STHLM.

“How I do wonder about the future?”

LETTERS TO THE FAMILY 1932–1933

Signe Hammarsten Jansson at her desk. In the background is Viktor Jansson’s marble head of a six-year-old Tove, and to the right of it a photograph of her that was used on some of the first Moomin books.

Per Olov Jansson and Viktor Jansson in Helsinki in the 1940s. Per Olov was called up in March 1940.

TOVE JANSSON’S LETTERS TO THE HAMMARSTEN JANSSON FAMILY in Helsinki are divided into two periods. The first includes letters from Stockholm 1932–33 and two long sequences of letters from Tove Jansson’s travels before the war, to Paris (1938) and Italy (1939). The second comprises letters from Tove Jansson to her mother, Signe Hammarsten Jansson, written after the death of her father Viktor Jansson in 1958.

When Tove Jansson is sixteen, she goes to Stockholm to study at Tekniska skolan, the Technical School, now the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design. There she attends a three-year course in drawing for advertising and design, lasting from 1930 to 1933. While she is studying in the city, she lives with her maternal uncle Einar Hammarsten and his family, his wife Anna-Lisa and his daughter Ulla. Their address is Norr Mälarstrand 26, within walking distance of the school in Mäster Samuelsgatan.

Tove Jansson writes her first letters to her family in Helsinki during her time in Stockholm. They are interiors from her final year as a student at “Teknis” and from daily life in her uncle’s family. There are stylistic parallels with the diaries Tove Jansson kept at the same time – the rather nonchalant, impromptu attitude she adopts for reporting on herself and her projects – yet at the same time her letters express the respect for work that characterises her life and all her activities. The importance of her close family and wider circle of relations is striking, both in the affection with which, in the letters, she addresses her close family in Helsinki and in her accounts of the Hammarsten branch of the family in Stockholm. In the small number of letters that have survived (all from 1932–33), the sense of responsibility she feels towards her family is palpable. One senses friction between her fascination with fine art and the necessity of training for a profession. Tove Jansson is thrown into helping provide for her family at an early age. “I have to become an artist for the family’s sake,” she writes in her diary in 1931, her first year in Stockholm. In the very first letter in this volume (4.12.1932), Tove Jansson writes to her “Beloved Papa and Mama” to tell them about the hectic weeks at the school just before Christmas and how much she looks forward to coming home to Helsinki.

Her parents had met each other in 1910 in Paris, where they were both studying art. They married in 1913 – on Blidö in the Stockholm archipelago, where Signe Hammarsten’s parents had a summer house – and moved into 4B Lotsgatan in Helsinki/Helsingfors. Their daughter Tove Marika was born on 9 August 1914 and she had two brothers, Per Olov, born in 1920, and Lars, born in 1926. In 1933, the family moved to the Lallukka artists’ house, which had just been built at 13 Apollogatan. For the summer they rented a house in the Pellinge archipelago, just outside Borgå.

Viktor Jansson (1886–1958) was born and raised in Helsinki. His father, Julius Victor Jansson, had been employed at the Stockmann department store and later owned a haberdashery shop. His mother’s name was Johanna Karlsson. They had four children, but only Viktor and his brother Julius (known as Jullan), survived. Viktor’s father died when Viktor was six, leaving the family in straitened circumstances. But Johanna Karlsson – who received a full secondary education and continued her studies at a school of commerce – ran the shop and made sure her boys were educated, too. The shop later went bankrupt, but by then Viktor had trained at the Finnish Art Association’s school of drawing in Helsinki and been to Paris on an art scholarship. Since his youth, Viktor Jansson had been known as “Faffan”, a name that was also used within the family.

Signe Hammarsten (1882–1970) was born in Hannäs in Sweden and was the daughter of a clergyman. The family moved to Stockholm when she was in her early teenage years. Her father, Fredrik Hammarsten, was later appointed vicar at the Jakob church in the centre of Stockholm. Signe Hammarsten was the second of six children, having an older sister and four younger brothers. She dreamt of becoming a sculptor, but the family’s economy would only stretch to a full education for the sons. Instead she had to make do with an art course at the Advanced School of Applied Arts (which she financed herself by working), a section of the Technical School that trained teachers of drawing. She later took up a teaching post at the Wallin school in Stockholm and was known for setting up a Scouting group for girls with two colleagues, before the official founding of the Girl Scout movement in 1911. After her marriage to Viktor Jansson, Signe Hammarsten Jansson, who worked under the name “Ham”, became well known in Finland for her drawings and caricatures and her designs for postage stamps. She was also known as Ham within the family.

In this volume, Signe Hammarsten’s siblings and their families feature in Tove Jansson’s letters to the family and also those to other addressees. The eldest of the children was Elsa Hammarsten. She married a German clergyman, Hugo Flemming, and left Sweden. Tove went to visit her and her family when she was on a trip to Germany in the summer of 1934. The Hammarsten brothers – Torsten, Olov, Einar and Harald (known as H2) – all went into branches of the sciences. One became a mining engineer, the others a biologist, a chemist and a mathematician. They had an aura of adventure and excitement about them, especially Torsten, Einar and Harald, whose frequently explosive natures made quite an impression on their niece. They are vividly described in the short story “Mina älskade morbröder” (My Beloved Uncles) in the 1998 collection Meddelanden (Messages). The letters tell us about Ängsmarn, the house on Blidö in the northern Stockholm archipelago where the Hammarsten family spent its summers. The uncles built assorted houses there, while their sister Elsa would take up residence in the one their parents Fredrik and Elin Hammarsten had built when they bought the plot in 1905. The Jansson family would come to visit over the summer and, in her time as a student in Stockholm, Tove Jansson was often on Ängsmarn. In the first chapter of Bildhuggarens dotter (1968, The Sculptor’s Daughter) –

which opens with the words “Grandfather was a clergyman and used to preach to the King” – the setting unfolds as if in a creation myth.

Viktor Jansson’s family did not get to see the young Tove Jansson quite so often and visits to the Jansson clan are not described at any length in her diaries. But Viktor’s brother and his family feature in the letters, and Tove Jansson the adult writer slips a canny paternal grandmother with a button shop into The Sculptor’s Daughter.

The letters to the family are often directed to her mother – addressed as “Beloved Mama” or “Beloved” – but a number are written to both parents and some to “Beloved everybody”. Reading the letters reveals clearly that they were intended for the whole family. Tove Jansson writes, for instance, to her “own beloved papa” on 27.3.1938: “Correspondence usually goes via Mama, of course, but I know you all speak to me through her letters and I often take them as being ‘from the family’, just as my answers are intended for all of you.” She often signed the letters “Noppe”, a pet name she had within the family.

* * *

SUN. 4 DEC. STHLM. [1932]

Beloved Papa and Mama!

Seeing as it is Sunday evening, and about two weeks until I leave and a week since I last wrote, I think I can let myself tell you all the bits of silly nonsense that have been going on here. It’s always so busy anyway as Christmas approaches and I don’t really know whether I like the way time starts speeding by. Apart from the snow, which is stubbornly late, all the signs of Christmas have arrived. Drottninggatan and Regeringsgatan are swathed in garlands and lights as usual, and every last little tobacconist’s has its share of cotton wool and tinsel in the window.

Comet in Moominland

Comet in Moominland Moominvalley in November

Moominvalley in November Moominland Midwinter

Moominland Midwinter Moominpappa's Memoirs

Moominpappa's Memoirs Sculptor's Daughter

Sculptor's Daughter The Listener

The Listener Tales From Moominvalley

Tales From Moominvalley Letters from Tove

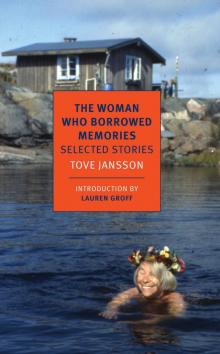

Letters from Tove The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories Travelling Light

Travelling Light Finn Family Moomintroll

Finn Family Moomintroll Moominsummer Madness

Moominsummer Madness Moominpappa at Sea

Moominpappa at Sea Fair Play

Fair Play Letters From Klara

Letters From Klara Art in Nature

Art in Nature The Moomins and the Great Flood

The Moomins and the Great Flood The Exploits of Moominpappa

The Exploits of Moominpappa The Woman Who Borrowed Memories

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories