- Home

- Tove Jansson

Moominpappa's Memoirs

Moominpappa's Memoirs Read online

PUFFIN BOOKS

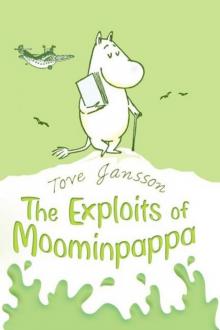

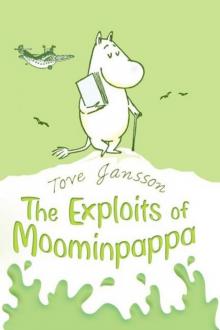

The Exploits of Moominpappa

Tove Jansson was born in Helsingfors, Finland, in 1914. Her mother was a carcaturist (and designed 165 of Finland’s stamps) and her father was a sculptor. Tove Jansson studied painting in Finland, Sweden and France. She lived alone on a small island in the gulf of Finland, where, most of her books were written.

Tove Jansson died in June 2001.

Other books by Tove Jansson

FINN FAMILY MOOMINTROLL

COMET IN MOOMINLAND

MOOMINLAND MIDWINTER

MOOMINSUMMER MADNESS

MOOMINVALLEY IN NOVEMBER

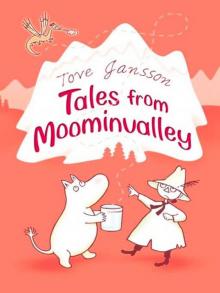

TALES FROM MOOMINVALLEY

Set down and illustrated by

Tove Jansson

The Exploits of Moominpappa

Described by Himself

Translated by Thomas Warburton

PUFFIN BOOKS

PUFFIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published in English by Ernest Benn Ltd 1952

Published in Puffin Books 1969

21

Copyright 1952 by Tove Jansson

English translation copyright © Ernest Benn Ltd, 1966

All rights reserved

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-14-191565-4

CONTENTS

PREFACE

CHAPTER 1

In which I tell of my misunderstood childhood, of the tremendous night of my escape, of the building of my first Moominhouse, and of my historical meeting with Hodgkins.

CHAPTER 2

Introducing the Muddler and the Joxter, and presenting a spirited account of the construction and matchless launching of the houseboat

CHAPTER 3

Recapitulating my first heroic exploit, its staggering outcome, a few thoughts, and my first confrontation with the Niblings.

CHAPTER 4

In which the description of my Ocean voyage culminates in a magnificent tempest and ends in a terrible surprise.

CHAPTER 5

In which (besides giving a little specimen of my intellectual powers), I describe the Mymble family and the Surprise Party which brought me some bewitching tokens of honour from the hand of the Autocrat.

CHAPTER 6

In which I become a Royal Outlaw Colonist and show remarkable presence of mind when meeting the Ghost of Horror Island.

CHAPTER 7

Describing the triumphant unveiling of the Amphibian and its sensational trial dive to the bottom of the sea.

CHAPTER 8

In which I give an account of the circumstances of the Muddler’s wedding, further touch on the dramatic night when I first met Moominmamma, and finally write the remarkable closing words of my Memoirs.

EPILOGUE

MOOMIN-GALLERY

PREFACE

I, MOOMINPAPPA, am sitting tonight by my window gazing into my garden, where the fireflies embroider their mysterious signs on the velvet dark. Perishable flourishes of a short but happy life!

As a father of a family and owner of a house I look with sadness on the stormy youth I am about to describe. I feel a tremble of hesitation in my paw as I poise my memoir-pen.

Still, I draw strength from some words of wisdom I have come across in the memoirs of another remarkable personage: ‘Everyone, of whatever walk in life, who has achieved anything good in this world, or thinks he has, should, if he be truth-loving and nice, write about his life, albeit not starting before the age of forty!’

I feel rather nice, and I like truth when it isn’t too boring. I will attain the suitable age on 9 August.

Yes, I really think I must yield to Moomintroll’s persuasion and to the temptation of talking about myself, of getting into print and being read all over Moominvalley! May my simple notes bring delight and instruction to all Moomins, and especially to my dear son, even if my memory isn’t quite what it has been.

And you, foolish little child, who think your father a dignified and serious person, when you read this story of three daddies’ adventures you should bear in mind that one daddy is very like another (at least when young).

I believe many of my readers will thoughtfully lift their snout from the pages of this book every once in a while to exclaim: ‘What a Moomin!’ or: ‘This indeed is life!’

Last but not least I want to express my heartfelt thanks to the people who most of all contributed to forming my life into the work of art it has become: Hodgkins, the Hattifatteners, and my wife, the matchless and exceptional Moominmamma.

Moominvalley in August

CHAPTER 1

In which I tell of my misunderstood childhood, of the tremendous night of my escape, of the building of my first Moominhouse, and of my historical meeting with Hodgkins.

ONE cold and windy autumn evening many years ago a newspaper parcel was found on the doorstep of the Home for Moomin Foundlings.

In that parcel I lay, quite small and shivering with cold, and without the least idea of where my father and mother were. (I’ve thought sometimes how much more romantic it would have been if mother had only laid me instead on green moss, in a small straw basket. But she probably hadn’t any.)

The Hemulen who had built the Foundlings’ Home snorted her customary snort and clamped a numbered seal on my tail to avoid mixing me up with the other Moomin-children. There were a lot of us, and we all soon became grave and tidy youngsters, because the Hemulen had a most solid character and used to wash us more often than she kissed us.

Still, she had one little weakness; she was interested in astrology, and every time a Moominchild was found on her doorstep she observed the position of the stars. They seem to be most important things!

Just imagine – had I come into the world only half an hour later I would have felt compelled to join the Hemulic Voluntary Brass Band, and one day earlier only gamblers were born. (Mothers and fathers should keep such things well in mind.)

But when the Hemulen looked at my stars she just shook her head and exclaimed: ‘This will be no easy Moomin. He’s overtalented.’

I think she was right (except that I have always felt at ease with myself).

I’ll never forget the house we lived in. It wasn’t like a Moominhouse at all. No surprising nooks and corners, no secret chambers, no stairs, no balconies, no towers. The Foundlings’ Home was bleak and square, and it stood on a lonely heath.

I remember the fog, and the cries of the night birds, and the lonely trees on the horizon – and dark corridors with rows and rows of doors opening on sq

uare and beery-brown rooms. I remember that nobody was ever allowed to eat treacle sandwiches in bed or to keep pets under it, or to get up at night for a walk and chat.

I remember the dismal smell of oatmeal soup. And just imagine that you had to carry your tail at a certain angle when saying ‘good morning’ to the Hemulen!

‘Have you washed your ears?’ she inquired. ‘Whatever are you thinking of?’ she asked. ‘Please be sensible!’ she said.

I wasn’t sensible. At first I was only unhappy.

I used to stand before the mirror and look deep in my unhappy eyes and heave sighs such as: ‘Oh, cruel fate!’

‘Oh, terrible lot.’ ‘Nevermore.’ And in a few minutes I felt a little better.

But then spring came…

It came all at once. Shoots and sprouts pushed dazedly out of the ground, crumpled like the ears of new-born Moominchildren. New winds were singing at night, and the world was full of all kinds of whirring, chirping, and humming noises. Everything was new once again.

And one day I heard a calm, regular thunder far away. The sea had shed its ice, and the surf was breaking on the shore. But we were never allowed to go to the shore.

I walked about, all alone, thinking.

I thought of everything I’ve just described to you. Of stars, Hemulens, square rooms, tail-seals, and the surf. And I expect you’ll understand that I decided to run away. There simply wasn’t anything else to do.

The escape was easy, almost too easy.

I had only to wait until everybody was asleep. Then I silently opened my window and made fast the Hemulen’s clothes-line to the ledge. Very silently I slipped down to the wet ground and stood there listening. The surf was there as before, and so were all the night sounds. I had never heard them more clearly.

But before I left I laid a letter on the same doorstep where I had once been found in a newspaper parcel. It read:

Dear Hemulen,

I feel great events awaiting me. Life is short, the world is enormous. Perhaps I shall return one day decked in laurel wreaths. So long, and all best wishes from

A Moomin who is unlike others.

PS. I’m taking a pot of pumpkin mash with me.

I’m still of the opinion that it was a good letter, deeply and strongly worded. I expect the Hemulen’s conscience gave her a good pinch.

And so I went. Straight into the night, all alone and a little afraid – but not much. I think.

*

At this point in his Memoirs Moominpappa was very deeply moved by the tale of his unhappy childhood, and he felt that he needed a rest. He screwed the top on his memoir-pen and went over to the window. All was silent in the Valley of the Moomins.

A light breeze was whispering in the silver poplars and gently swinging Moomintroll’s rope ladder to and fro. ‘I’m sure I’d manage an escape still if I needed to,’ Moominpappa thought ‘Who cares if I’m not as young as I used to be!’

He chuckled to himself. Then he lowered his slightly rheumatic legs over the window ledge and reached for the rope ladder.

It swung about and he had great difficulty in keeping his balance.

‘Drat the thing,’ said Moominpappa softly, beginning to feel giddy.

‘Hullo, Father,’ said Moomintroll at the next window. ‘What are you up to?’

‘Exercises, my boy,’ answered Moominpappa. ‘Keeping fit! One step down, two up, one down, two up. Good for the muscles.’

‘Better be careful,’ said Moomintroll. ‘How are the Memoirs going?’

‘Very well,’ answered Moominpappa and hauled his trembling legs into safety over the window ledge. ‘I’ve just run away. The Hemulen cries with grief. I think it will be very moving.’

‘When are you going to read it to us?’

‘Soon. As soon as I’m sure it’s going to be a best-seller. Bring Sniff and Snufkin the day after tomorrow to hear the first chapter. There’s nothing more pleasant than reading your own book aloud!’

‘I suppose not,’ said Moomintroll and stifled a yawn. ‘Well, good night, Father!’

‘G’night, Moomintroll,’ answered Moominpappa, already unscrewing the top of his memoir-pen.

*

Well. Where was I… Oh yes, I had run away, and then in the morning – no, that was a little later.

All the night I wandered through that strange and gloomy country. I didn’t dare stop to rest; I didn’t even dare look around me. I might have caught sight of something in the darkness! Sometimes I tried to whistle, to show myself that it wasn’t so bad. But my voice trembled so much that it only frightened me all the more. But as for going back – never in the world! Not after such an imposing letter of farewell.

And finally the misty night came to an end. When the sun rose something very beautiful happened. The first bunches of sunlight suddenly made the mist as rosy-red as the veil on the Hemulen’s Sunday bonnet. In a moment the whole world became pink and friendly-looking!

I halted and saw the night dissolve itself in thin glowing veils. Cobwebs and wet leaves were heavy with glistening rubies. My heart turned a somersault for pure happiness. Ho! I tore the hateful seal from my tail and threw it far away among the heather. And there and then I danced the Moomin dance of dawning freedom in the dewy and glistening spring morning, with my nice small ears pucked and my snout lifted against the sky.

No more washing by others’ orders! No more eating just because it was dinner-time! No more saluting anybody other than a King (I’m a staunch royalist, in case you didn’t know), and no more sleeping in square, beery-brown coloured rooms! Triumph!

First of all I ate the pumpkin mash and tossed the pot away. Now I had nothing to call my own. I knew nothing, but believed a lot. I did nothing by habit. I was extremely happy.

And I walked and walked and walked along the winding and wriggling path, and once more evening came, and then it was night again with a wind and a gale.

The night was black as pitch; I heard rustling and crackling all about me, and great wings went whispering and swishing over my head. The ground became uneven and soft, and I lost the path. A strange and nice smell filled the air and my snout with expectation. I didn’t know yet that it was the wood’s perfume of moss, bracken, and wet leaves. I felt very tired when I curled up and tried to warm my cold paws against my stomach. The great orchestra of the gale played overhead, and in the moment I went to sleep I thought: ‘Tomorrow!’

When I awoke I lay on my back looking straight up into a world of green and gold and white. The trees around me were tall and strong pillars that lifted their green roof to a dizzying height. The leaves swayed gently and glittered in the morning light, and a lot of birds were dashing, giddy with delight, through the shafts of sun. Gleaming white honeysuckle hung everywhere in bunches and curtains from the branches. Gold and green and white! I stood on my head for a moment to calm myself.

Then I shouted:

‘Hello! Who does this place belong to?’

‘Don’t bother us! We’re busy playing!’ the birds screeched back.

I went farther into the wood. In the shade of the giant bracken there were swarms of small creatures jumping and flying about. But they were too small to understand serious conversation.

At last I met a hedgehog who was busy polishing a large nutshell.

‘Good morning, ma’am,’ I said. ‘I’m a lonely refugee who was born under rather special stars.’

‘Really,’ said the hedgehog, not too enthusiastically. ‘Pretty shell, isn’t it? It’s going to be a milk-bowl.’

‘Very pretty,’ I said. ‘Who owns this place?’

‘Why, nobody! Or everybody, I suppose,’ said the hedgehog.

She seemed surprised.

‘Me, too?’ I asked.

‘By all means,’ said the hedgehog and continued her polishing.

‘Are you quite sure that it doesn’t belong to some Hemulen or other?’ I asked, a little worriedly.

‘Hemulen?’ said the hedgehog. ‘What’s that?’

‘A Hemulen reaches almost double the height of ordinary bracken,’ I explained. ‘Snout protruding and slightly depressed. Pink eyes. No ears, but instead a couple of tufts of ginger-coloured or blue hair. The Hemulen isn’t outstandingly intelligent and easily becomes a fanatic. Her feet are terribly large and flat. She cannot learn to whistle, and so dislikes all whistling. She…’

‘Oh, good gracious,’ said the hedgehog and backed away among the bushes.

‘Well,’ I thought. ‘Probably they have no Hemulens here. Nobody’s place and everybody’s place. Mine, too. What shall I do?’

The idea came to me all at once, as is usually the case. (I just hear a faint ‘click’, and there it is.) Given a Moomin and a place, and there must follow a house. I was going to build a house with my own hands, a house exclusively my own!

I built it by the brook, where the grass was green and soft and exactly suitable for a Moomin-garden. All around it dense thickets stood in full bloom, trailing their boughs in the water.

My first Moominhouse arose with mysterious speed. That must have been due to inherited ability, but also to talent, good judgement and a sure taste. But one mustn’t indulge in self-praise, so I’ll only give you a simple sketch of the result.

It was quite a small house, but tall and slender as a Moominhouse should be, and adorned with several balconies, stairs, and turrets. The hedgehog lent me a fret-saw to do the pine-cone pattern on the verandah balustrade. As for the porch, I had to leave out the brass doors, of course, but even without them my house unmistakably resembled a porcelain stove of the genuine old kind. (You see, we Moomins always try to preserve the style from old times, when we used to live behind porcelain stoves. That was before central heating.) And when it was finished I went downstairs again feeling very contented. It was a kind of last farewell to the Hemulen.

But after a while I discovered that I was feeling slightly bored in some strange way. This surprised me and even made me angry with myself. But there it was. And believe

Comet in Moominland

Comet in Moominland Moominvalley in November

Moominvalley in November Moominland Midwinter

Moominland Midwinter Moominpappa's Memoirs

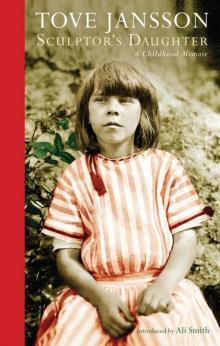

Moominpappa's Memoirs Sculptor's Daughter

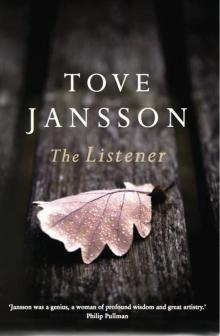

Sculptor's Daughter The Listener

The Listener Tales From Moominvalley

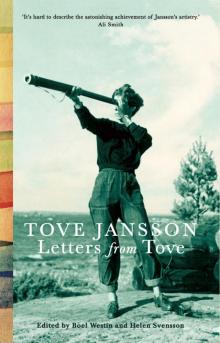

Tales From Moominvalley Letters from Tove

Letters from Tove The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories Travelling Light

Travelling Light Finn Family Moomintroll

Finn Family Moomintroll Moominsummer Madness

Moominsummer Madness Moominpappa at Sea

Moominpappa at Sea Fair Play

Fair Play Letters From Klara

Letters From Klara Art in Nature

Art in Nature The Moomins and the Great Flood

The Moomins and the Great Flood The Exploits of Moominpappa

The Exploits of Moominpappa The Woman Who Borrowed Memories

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories