Comet in Moominland

Comet in Moominland Moominvalley in November

Moominvalley in November Moominland Midwinter

Moominland Midwinter Moominpappa's Memoirs

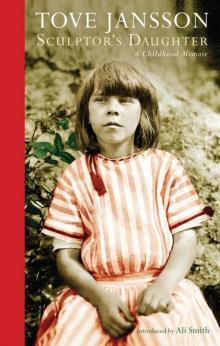

Moominpappa's Memoirs Sculptor's Daughter

Sculptor's Daughter The Listener

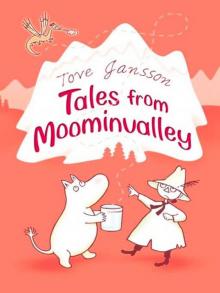

The Listener Tales From Moominvalley

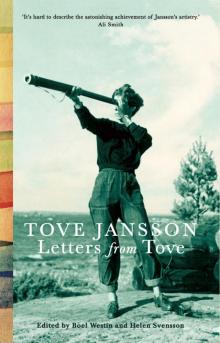

Tales From Moominvalley Letters from Tove

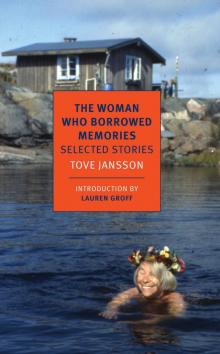

Letters from Tove The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories Travelling Light

Travelling Light Finn Family Moomintroll

Finn Family Moomintroll Moominsummer Madness

Moominsummer Madness Moominpappa at Sea

Moominpappa at Sea Fair Play

Fair Play Letters From Klara

Letters From Klara Art in Nature

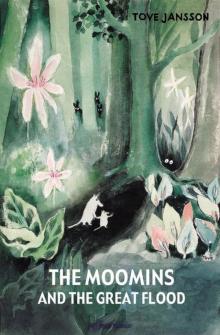

Art in Nature The Moomins and the Great Flood

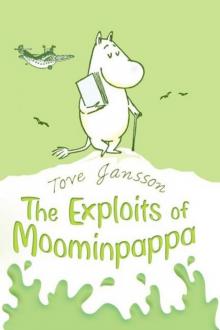

The Moomins and the Great Flood The Exploits of Moominpappa

The Exploits of Moominpappa The Woman Who Borrowed Memories

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories