- Home

- Tove Jansson

The Exploits of Moominpappa Page 2

The Exploits of Moominpappa Read online

Page 2

me, boredom when you ought to enjoy yourself is the worst kind of boredom.

I went and called on the hedgehog.

‘Well?’ she said. ‘Only don’t say a word about Hemulens.’

‘No, no,’ I said. ‘But won’t you come and look at my house? We could sit there for a while and have a chat. I’ll tell you all about my strange birth.’

‘That would be fascinating,’ said the hedgehog. ‘I’m so sorry I haven’t got the time. I’m making milk-bowls for all my daughters.’

And that went for all the people in the wood. The birds, the worms, the tree-spirits, and the mousewives seemed to be in a great hurry about something or other. Nobody wanted to look at my house, or hear about my escape, or about the strange way I came into the world.

I went back to my green garden by the brook and sat down on the verandah. My verandah. My lonely fretwork verandah.

And suddenly – click – I had a new idea: to find out where the brook led.

I stepped into the cool water and began wading downstream. The brook ran as brooks do; with many freaks and

no hurry. Sometimes it rippled along, clear and shallow, over lots and lots of pebbles, and sometimes the water darkened and rose up to my snout. There were blue and red water-lilies floating everywhere in the stream. The sun was already setting and shone straight in my face. And after a while I began to feel almost happy again.

Then I heard a funny little whirring noise. Straight in front of me a splendid water-wheel was spinning. It was made of small sticks and stiff palm-leaves.

And somebody said: ‘Please be careful.’

I looked up and saw a couple of hairy ears in the long grass by the brook.

‘I’m just looking,’ I said. ‘Who are you?’

‘Hodgkins,’ said the owner of the ears. ‘And you?’

‘The Moomin,’ I said. ‘A lonely refugee born under rather special stars.’

‘What stars?’ asked Hodgkins, and his question made me very happy, because it was the first time anybody had asked me something I wanted to answer.

So I went to the shore and sat down at his side, and there I told him everything that had happened to me since the day I was found in the newspaper parcel. (Only I told him it had been a small basket of leaves.) And all the time the water-wheel was spinning in a little cloud of glittering waterdrops, and the sun reddened and sank, and my heart found new peace and happiness.

‘Strange,’ said Hodgkins when I had finished. ‘Rather strange. That Hemulen. Bit of a cad, I think.’

‘Quite,’ I said.

‘Not many worse, are there?’ said Hodgkins.

‘Certainly not,’ I said.

Then we were silent for a while and looked at the sunset.

It was Hodgkins who showed me how to construct a water-wheel, an art that I have later taught my son. (Cut two forked branches and stick firmly in stream. Sandy bottom is best. Choose four stiff leaves, cross to form a star, pierce with stick. Strengthen construction with twigs. Carefully place stick on forks, and wheel will turn.)

In the evening twilight Hodgkins and I walked back to my house and I asked him in.

He said it was a good house. (Thereby he meant that it was a wonderful and fascinating house. Hodgkins never cared much for big words.) The night wind came and sang us a song.

I had now found my first friend, and so my life was truly begun.

CHAPTER 2

Introducing the Muddler and the foxter, and presenting a spirited account of the construction and matchless launching of the houseboat.

WHEN I awoke the following morning Hodgkins was already casting a net in the brook.

‘Hello,’ I said. ‘Any fish here?’

‘Hardly,’ said Hodgkins. ‘Still, we might catch something else. Want to come and meet the Muddler?’

We locked the door and went.

The Muddler lived quite near. He was very small and muddly, Hodgkins told me, and he had made himself at home in an American coffee tin; the blue kind.

‘Is he a relative of yours?’ I asked.

‘My nephew,’ Hodgkins said. ‘Adopted him. Father and mother disappeared in a spring-cleaning.’

‘How terrible,’ I said. ‘Were they never found?’

‘Never,’ Hodgkins answered.

He took out his cedarwood whistle that had a pea inside, and whistled twice.

The Muddler came running at breakneck speed, trying to beat his tail and flap his ears and whisk his whiskers at the same time.

‘Evening!’ he cried. ‘Why, that’s grand! Whom are you bringing? Gee, what an honour! Excuse me please, things are a bit upside-down in my tin, but if you’d just…’

‘Never mind,’ Hodgkins said. ‘We’re just out for a walk. Want to come along?’

‘Why, sure!’ the Muddler cried. ‘Just a minute, please, I’ll have to bring a few things along…’

And he disappeared inside his tin where we heard him start a terrific rummaging. After a while he came out again carrying a wooden box under his arm, and so we all walked along together through the wood.

‘Dear nephew,’ Hodgkins suddenly said. ‘Can you paint?’

‘Can I paint!’ exclaimed the Muddler. ‘Sure, I’ve painted portraits of all my cousins! A separate portrait of each and every one! Excuse me, do you need some extra special, A-I de-luxe painting done?’

‘You’ll see. It’s a secret so far,’ Hodgkins answered.

At that the Muddler became so excited that he started jumping about on his toes, and the string around his box snapped, and out tumbled a heap of his personal belongings, such as wire springs, paper clips, ear-rings, tins, dried frogs, cheese-knives, trouser-buttons, and pipe-cleaners, among other things.

‘Well, well,’ said Hodgkins and helped him to collect it all again.

‘I had a really dandy piece of string once, only I lost it somewhere! Excuse me!’ the Muddler said.

Hodgkins produced a strong length of rope and tied it around the box, and so we walked on again.

Finally, he halted by a large fig thicket and said:

‘Enter, please.’

We made our way through the green bushes, stopped, turned our heads upwards, and exclaimed respectfully: ‘A ship!’

It looked large and deep and strong, and its blunt stem disappeared out of sight somewhere in the shadows of the thicket.

‘My houseboat,’ Hodgkins said.

‘Your what?’ I asked.

‘Houseboat,’ Hodgkins repeated. ‘A house built aboard a boat Or a boat built beneath a house. You live aboard. Nice and practical.’

‘And where’s the house?’ I asked.

Hodgkins let his paw describe a sweeping gesture, ‘Your house by the brook,’ he said.

‘Hodgkins,’ I replied, feeling a catch in my throat, ‘when our mutual talents are joined there’ll be no limit to their scope.’

By this time the Muddler had regained his breath and was able to shout: ‘Gee, is it really true? Oh! May I paint that ship? Cross your heart?’

‘Cross my heart, yes. Choose your own colour,’ Hodgkins replied. ‘But be careful about the water-line. And her name is The Ocean Orchestra. That’s the title of my long-lost brother’s book of poems. You’ll have to paint the name marine blue.’

Glorious times! Immortal deeds! Triumphantly we marched back to my house and began moving it to the shipyard. ‘Grab hold now,’ said Hodgkins. ‘Easy does it… Raise a bit more on that side! Now she moves…’

‘Careful with the verandah, please!’ I cried.

‘Excuse me! The cellar got on my toes!’ shouted the Muddler. And as he said it the house tipped up and a person came tumbling out of an upper window.

We looked at him.

‘Hello!’ I said threateningly.

‘Hello yourself,’ said the Joxter (for it was he).

‘Why did you enter my house?’ I continued.

The Joxter took his pipe from his mouth and explained genially: ‘Because you had loc

ked the door.’

‘Sure, that’s him all over!’ cried the Muddler. ‘He likes everything you mustn’t do. He’s always fighting policemen and laws and traffic signs.’

‘And park keepers,’ completed the Joxter, ‘Has anybody had any breakfast yet?’

‘No, quite the contrary,’ said Hodgkins. ‘Nephew! That pudding. Anything left?’

‘Sure,’ said the Muddler. ‘Seen it yesterday.… Of course, my house is small and unworthy – but still – if I run along now and tidy it up a bit…’

And the Muddler clutched his box tightly under his arm and rushed off.

‘Somebody hold the verandah,’ said Hodgkins. ‘I think we’ll manage. We’ll take the boathouse to the houseboat and have breakfast afterwards.’

‘Isn’t the Joxter going to help?’ I asked (because I was still a little cross with him).

‘Born lazy,’ explained Hodgkins. ‘Has to be forbidden to lend a hand. Then does it. Possibly.’

And then the auxiliary engine wouldn’t work. The paddles refused to turn the screw, and not even my mind was able to cope successfully with the problem. (My modesty compels me to admit that there are three fields where my genius appears to feel somewhat cramped, namely, engineering, mathematics, and cookery.)

The Muddler had fried us an omelette, because he had lost the pudding somewhere.

‘O.K.?’ he asked anxiously and looked at Hodgkins.

Hodgkins was chewing most carefully with a strange look on his face. Finally he said: ‘These knobbly things. Stuffing, what?’

‘Knobbly things!’ cried the Muddler. ‘That must be something from my collection. Spit them out, please!’

Hodgkins deposited them on his plate. They were black and bevelled and prickly.

‘Oh, please excuse me!’ cried the Muddler. ‘It’s my cogwheels. What luck you didn’t swallow them!’

But Hodgkins didn’t answer him. He frowned deeply and sat looking down at his plate.

Then the Muddler started to cry.

‘Hodgkins, you’ll have to forgive the Muddler,’ said the Joxter. ‘Can’t you see that he’s really sorry?’

‘Forgive him?’ said Hodgkins. ‘My nephew has earned a medal.’ And he produced a pencil and some paper and showed us where the bevelled cogwheels would make the screw turn. He drew it like this:

(I saw the point at once, but the others had to study it for a while.)

‘You don’t mean that you need my cogwheels for your invention?’ cried the Muddler blissfully. ‘Then I’ve almost built the auxiliary engine myself!’

The Muddler was so inspired by this that he donned his largest pinafore and started to paint The Ocean Orchestra at once. He painted with all his might. The houseboat was quite red when he had finished, and so was the ground, and most of the shipyard, too; and never in my life have I seen anything redder than the Muddler himself.

When it was all finished Hodgkins came for an inspection.

‘Isn’t it beautiful?’ the Muddler said nervously, ‘I’ve worked very carefully.’

Hodgkins looked at the water-line and said: ‘Mphm.’ Then he looked at the name on the prow and said: ‘Mphm, mphm.’

‘Is the spelling wrong?’ asked the Muddler. ‘Please say something or else I shall start crying again. Excuse me! It wasn’t an easy name!’

‘The Oshun, Oxtra,’ spelled Hodgkins. ‘Well. Well, well. Oh, yes. And why not? The water-line… I suppose the waves will fit in quite nicely. I see there’s some paint left. Keep it.’

Then the Muddler was happy again and rushed away to paint his house.

And in the evening Hodgkins tried his net in the brook. And what did he find? You couldn’t guess. A small binnacle, and inside it a brand new aneroid barometer! How strange to find such things in our little brook!

*

‘Strange indeed,’ said Moomintroll. He lay on his back beneath the lilac bushes looking at the bumblebees.

‘Father,’ he continued. ‘Is it really quite true, all that you have written? Every word?’

‘Every single word of it, my boy,’ Moominpappa replied solemnly. ‘I may have stressed some of the events a little, but that’s only to make them more convincing.’

‘I wonder what became of my father’s collection,’ Sniff said.

‘Eh?’ said Moomintroll.

‘Father’s button collection,’ Sniff said. ‘The Muddler was my father, wasn’t he?’

‘Certainly,’ replied Moominpappa.

‘Well, then, I’m just wondering,’ Sniff said. ‘I ought to have inherited it.’

‘And what became of my father?’ asked Snufkin.

‘The Joxter?’ said Moominpappa. ‘Well, children, one doesn’t always know what happens to daddies… or to their collections. Still, I have saved yours for posterity by writing about them.’

‘He didn’t like park keepers either,’ mumbled Snufkin. ‘Just think of that…’

They all stretched out their legs in the grass and lazily flapped their ears to drive the flies away. The weather was nice and sleepy.

‘Have you written any more of it?’ asked Moomintroll.

‘Not yet,’ replied Moominpappa. ‘But if you can keep quiet now I’ll finish the chapter and read it to you after dinner. Where’s my memoir-pen?’

‘Here,’ said Snufkin. ‘Please promise that you’ll write the full truth and nothing but the truth about the Joxter! Even if he gets nabbed by the police.’

‘I promise,’ said Moominpappa, and continued his writing.

*

The day of the launching was unusually warm. Wonderful to behold The Oshun Oxtra resting in the shipyard on its four rubber wheels (for climbing sand banks), and on the roof of the boathouse shone a gilded knob.

‘So you’re moving again,’ said the Joxter and yawned. ‘What a life! No end of changing and building-up and pulling down again and jumping about. Such a lot of work may turn out to be really harmful. Oh, I’m dejected just to think of all the people who work and buzz and bumble about, and of what it all leads to. I had a cousin once who studied trigonometry until his whiskers drooped, and when he had learnt it all a Groke came and ate him up. When do we start?’

‘Are you coming, too?’ I asked.

‘Of course!’ said the Joxter in an astonished voice.

‘Please excuse me,’ said the Muddler, ‘but as it happens I had also something like that in mind… I can’t bear to live in my coffee tin any longer.’

‘No?’ I said.

‘That red paint never dries!’ explained the Muddler. ‘Excuse me! It gets in my food and in the bed and in my whiskers. I’m going plumb crazy, Hodgkins, plumb crazy!’

‘By all means don’t,’ said Hodgkins. ‘Go and pack. Because we are launching The Oshun Oxtra today.’

‘Gee!’ cried the Muddler. ‘Dear me, I have lots and lots to do! Such along journey… such a new life…’ And the Muddler rushed off spattering paint in all directions.

But the launching gave us much to think about. The wheels of the houseboat were sunk deep in the moss, and the mast was hopelessly stuck in the fig thicket.

We dug up the ground. We pulled down the shipyard. Still The Oshun Oxtra didn’t move.

Hodgkins sat down and put his head in his paws.

‘Don’t grieve. We’ll find a way’ I said.

‘I’m not grieving. I’m thinking,’ replied Hodgkins soberly. ‘This is the problem. A ship is stuck. Un-movable. You can’t push it in the river. Then the river must be pushed to the ship. How? You change its course. How? You damn it up. How? You pile stones in it.’

‘How?’ I asked.

‘NO!’ Hodgkins exclaimed with a force that made me jump. ‘No stones. Edward the Booble. Sits down in the river. Fills it up. Makes a dam.’

‘Is his behind so big?’ I asked.

‘Bigger,’ Hodgkins said. ‘Biggest animal in the world. Next to his brother. Have you a calendar?’

‘No,’ I said, beginning to feel excited.

‘Pea-soup, day before yesterday* Bathing-day today†,’ mused Hodgkins. ‘All clear then. Come along, Moomin.’

‘Are Boobies nice?’ I asked carefully as we walked along down the river beach.

‘Not very. But not dangerous either,’ said Hodgkins. ‘Tread on you only by mistake. Then weep for a week afterwards. And pay for the funeral too.’

‘No great help, that,’ I said, feeling rather brave (for if you’re not afraid how can you be really brave?).

‘Here he is,’ said Hodgkins suddenly.

‘Where?’ I said. ‘Does he live in this tower?’

‘No tower. It’s his leg,’ replied Hodgkins. ‘Keep quiet now, please. I’ll have to shout.’

And then he shouted at the top of his voice: ‘Ahoy, up there! Hodgkins down here! Mr Edward, where are you bathing this fine day?’

‘In the sea, of course, you sand flea,’ replied a thunder somewhere in the sky.

‘In the river! Running water! Excellent sand bottom!’ roared Hodgkins.

‘Lies and trumpery,’ said Edward the Booble. ‘Every mouseling knows the river is all full of stones.’

‘No, no! Nice and smooth!’ shouted Hodgkins back.

The Booble grumbled like a faraway thunderstorm. Then he said: ‘All right. I’ll bathe in the river. Get out of my way, I haven’t the money for any more funerals. And if you’ve tricked me you’ll have to pay for it yourself. You know I have such sensitive feet.’

‘Now!’ Hodgkins panted when we went running back. ‘He’ll sit down… in the river… angry… the water will rise… flooding the wood… and…’

‘Here it comes!’ I shouted, hearing a great splash in the distance.

We almost stumbled over the Joxter, who had curled himself up peacefully in the tool chest.

‘All aboard!’ cried Hodgkins. ‘Sleeping on my tools, indeed!’

And no sooner had we lifted our tails inside the railing

when the flood wave reached our houseboat. In a whirling cascade of white foam The Oshun Oxtra was carried free from all its entanglements and was ploughing along through the wood. The paddles swished, the screw turned. The Muddler’s cogs were functioning perfectly.

Comet in Moominland

Comet in Moominland Moominvalley in November

Moominvalley in November Moominland Midwinter

Moominland Midwinter Moominpappa's Memoirs

Moominpappa's Memoirs Sculptor's Daughter

Sculptor's Daughter The Listener

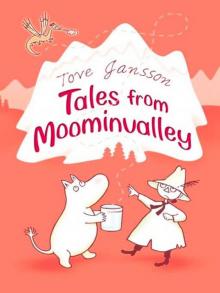

The Listener Tales From Moominvalley

Tales From Moominvalley Letters from Tove

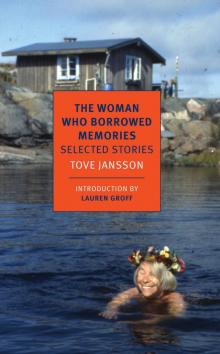

Letters from Tove The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories Travelling Light

Travelling Light Finn Family Moomintroll

Finn Family Moomintroll Moominsummer Madness

Moominsummer Madness Moominpappa at Sea

Moominpappa at Sea Fair Play

Fair Play Letters From Klara

Letters From Klara Art in Nature

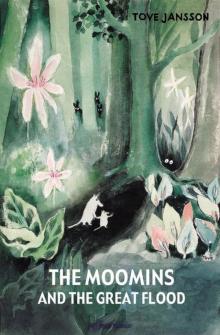

Art in Nature The Moomins and the Great Flood

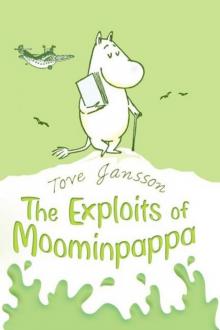

The Moomins and the Great Flood The Exploits of Moominpappa

The Exploits of Moominpappa The Woman Who Borrowed Memories

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories