- Home

- Tove Jansson

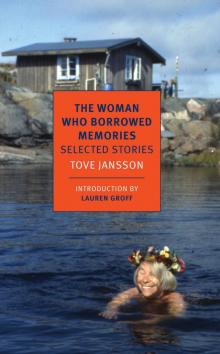

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories Page 27

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories Read online

Page 27

Look after your health very carefully.

I wish you a long life.

Tamiko Atsumi

Dear Jansson san

It’s been a long time, for five months and nine days you haven’t written to me.

Did you get my letters?

Did you get the presents?

I long for you.

You must understand that I’m studying very seriously.

Now I’ll tell you about my dream.

My dream is to travel to other countries and learn their languages and learn to understand.

I want to be able to talk with you.

I want you to talk with me.

You must tell me how you describe things without seeing other houses and with no one getting in the way.

I want to know how to write about snow.

I want to sit at your feet and learn.

I’m collecting money so I can travel.

Now I’m sending you a new haiku.

It’s about a very old woman who sees blue mountains far away.

When she was young she didn’t see them.

Now she can’t reach them.

That’s a beautiful haiku.

I beg you please be careful.

Tamiko

Dear Jansson san

You were going to go on a great long journey, now you’ve been traveling more than six months.

I think you’ve come back again.

Where did you go, my Jansson san, and what did you learn on your journey?

Perhaps you took with you a kimono.

In autumn colors and autumn is the time to travel.

But you’ve said so often that time is short.

My time grows long when I think of you.

I want to become old like you and have only big clever thoughts.

I keep your letters in a very beautiful box in a secret place.

I read them again at sundown.

Tamiko

Dear Jansson san

Once you wrote to me when it was summer in Finland and you were living on the lonely island.

You’ve told me that post hardly ever comes to your island.

Then do you get many letters from me at once?

You say it feels nice when the ships go by and don’t stop.

But now it’s winter in Finland.

You’ve written a book about winter, you’ve described my dream.

I’ll write a story to help everyone understand and recognize their own dream.

How old must you be to write a story?

But I can’t write my story without you.

Every day is a day of waiting.

You’ve said you’re so tired.

You work and there are too many people.

But I want to be the one who comforts you and protects your solitude.

This is a sad haiku about someone who waited too long for the one they loved.

You see how it went!

But it’s not so good in translation.

Has my English got any better?

Always

Tamiko

Much loved Jansson san, thank you!

Yes, that’s how it is, you don’t have to be a certain age, you just begin writing a story because you have to, about what you know or also about what you long for, about your dream, the unknown. O much loved Jansson san. One mustn’t worry about others and what they think and understand, because while you’re telling a story you’re only concerned with the story and yourself. Then you really are on your own. At this moment I know all about what it’s like to love someone far away and I will hurry to write about it before she comes nearer. I send you a haiku again, it’s about a little stream which becomes happy in spring so everyone listens and feels delight. I can’t translate it. Listen to me Jansson san and write to say when I can come. I’ve collected money and I think I’ll get a travel scholarship. What month would be best and most beautiful for our meeting?

Tamiko

Dear Jansson san

Thank you for your very wise letter.

I understand the forest’s big in Finland and the sea too but your house is very small.

It’s a beautiful thought, to meet a writer only in her books.

I’m learning all the time.

I wish you good health and a long life.

Your Tamiko Atsumi

My Jansson san

It’s been snowing all day.

I’m learning to write about snow.

Today my mother died.

When you’re the eldest in your family in Japan, you can’t leave home and don’t want to.

I hope you understand me. I thank you.

The poem is by Lang Shih Yiian, who was once a great poet in China.

It has been translated into your language by Hwang Tsu-Yii and Alf Henrikson.

“Wild geese scream shrilly on muffled winds.

The morning snow is heavy, weather cloudy and cold.

Poor, I can give you nothing in parting

but the blue mountains and they’ll always be with you.”

Tamiko

Translated by Silvester Mazzarella

LETTERS FROM KLARA

DEAR MATILDA,

You’re hurt because I forgot your venerable birthday. That’s unreasonable of you. I know the only reason you’ve looked forward to getting birthday greetings from me all these years is because I’m three years younger than you are. But it’s time you realized that the passing of the years isn’t in itself a feather in your cap.

You’re asking for Guidance from Above, excellent. But while you’re waiting for it to arrive, might it not be profitable to discuss a few bad habits which I have to admit aren’t totally alien to me, either.

My dear Matilda, one thing we should all remember is not to grumble if we can possibly help it, because grumbling immediately gives bad habits the upper hand. I know you’ve been fortunate enough to enjoy astonishingly good health, but you do have a unique capacity for giving those around you a bad conscience by grumbling, and then of course they hit back by cheerfully writing you off as someone who no longer matters. I know, I’ve seen it. Whatever it is you want or don’t want, couldn’t you stop whining? Why not try raising your voice instead and shaking them up with a few strong words or, best of all, scaring them a bit? I know very well you’re capable of it: There was never any mewing in the old days, far from it.

And all that stuff about not being able to get to sleep at night, presumably because you catnap eight times a day. Yes, I know; it’s true that memory has an unfortunate habit of working backwards at night and gnawing its way through everything without sparing the slightest detail—that you were too much of a coward to do something, for instance; that you made a wrong choice, or were tactless or unfeeling or criminally unobservant—but of course no one but you has given a thought for years to these things which to you are calamities, shameful actions, and irretrievably stupid statements! Isn’t it unfair, when we’re endowed with such sharp memories, that they only function in reverse?

Dear Matilda, do write and tell me what you think about these sensitive matters. I promise I’ll try not to be a know-it-all; oh yes, don’t deny it, you have called me that in the past. But I’d be fascinated to know, for example, what you do when you can’t remember how many times you’ve said the same thing to the same person. Do you extricate yourself by starting off “So, as I said . . .” or “As I may have already said . . .”? Or what? . . . Have you any other suggestions? Or d’you just keep quiet?

And do you let conversations you can’t follow continue over your head? Do you ever try to make a sensible contribution only to find that everyone else has moved on to a completely different subject? Do you try to save face by telling them they’re talking nonsense or wasting their time on matters too trivial to be worth discussing? In general, are we any of us in the least interested? Please reassure me that we are!

Only if you write to me, please don’t use that antediluvian fountain pen of yours; it make

s your writing illegible, and in any case it’s hopelessly out of date. Get them to buy you some felt pens, medium point 0.5 mm. You can get them anywhere.

Yours, Klara

P.S. I read somewhere that anything written in felt pen becomes illegible after about forty years. How about that? Good, don’t you think? Or are you planning to write your memoirs? You know the sort of thing: “Not to be read for fifty years” (I hope you think that’s funny).

Dear Ewald,

What a nice surprise to get a letter from you. What gave you the idea of writing?

Yes, of course we can meet; it’s been ages, as you say. Something like sixty years, I think.

And thank you for all the nice things you wrote—maybe a little too nice, my dear old friend. Hasn’t time made you a little sentimental?

Yes, I think growing roses is a great idea! I understand there’s a very practical gardening program on the radio every Saturday morning, repeated on Sundays. Why not listen to it?

Give me a call any time, but remember it may take me a while to get to the phone. And don’t forget to say whether you’re still a vegetarian, because I want to make us a really special dinner.

Yes, do bring your photograph album, I hope we’ll be able to have a reasonable stab at dealing with the inevitable “d’you remembers,” and then go on to talk about whatever comes into our heads.

Yours sincerely, Klara

Hi Steffy!

Thanks for the bark boat, it’s beautiful and it’s lovely to have it. I tried it out in the bath and it balances perfectly.

Don’t worry about that report, tell Daddy and Mommy it’s sometimes much more important to be able to work with your hands and make something beautiful.

I’m sorry about the cat. But if she lived to be seventeen she was probably quite tired and no longer very well. The words you wrote for her grave aren’t bad but you must take care with the rhythm. We’ll talk more about that when we meet.

Your godmother, Klara

Dear Mr. Öhlander,

In your letter of the 27th you claim that I am unjustifiably withholding from you an early work of your own, which you say you need to have, as soon as possible, for a retrospective exhibition.

I cannot remember that during a visit to your niece’s son I “wangled” the picture in question out of him; he is much more likely to have pressed me to remove it from his flat.

I have made a careful study of the signatures on the works I have around me here and can just about make out one which could possibly be your own. The picture seems to show something halfway between an interior and a landscape; one might say that there’s a je ne sais quoi of the semi-abstract about it.

The size, which you didn’t mention, is the classic French 50 × 61.

I’m restoring your work to you by return of post and I hope that it will now be able to take its rightful place in your collection.

Yours faithfully, Klara Nygård

Dear Nicholas,

I expect you’ve only just got back from your “mystery destination” (I have a strong feeling it was Majorca); be that as it may, I’ve decided to make yet another small change to my will. Don’t groan, I know that deep down all this to-ing and fro-ing amuses you.

Well, I want to make over a fixed annual sum to the Old People’s Home of whose services I shall one day be availing myself. But—and this is the important point—only during my lifetime. Interest from banks and bonds and whatever else, I can do without—you know more about that than I do. They can use the money in whatever way suits them best.

I’m sure you’ve got the idea, cunning as you are. This temporary extra income will make it worth their while, at the Home, to do their best to keep me alive as long as they can; I shall be their mascot and will obviously be able to take certain liberties. What’s left when I die will not go to them but must be divided up exactly as we planned earlier.

By the way, I’m in excellent health and I hope you are too.

Klara

My dear Cecilia,

It was so nice of you to send me my old letters; what an enormous box, did you at least have someone to help you get it to the post? It really touches me that you saved them all (and even numbered them), but, my dear, that business of reading them through—you understand what I mean? I suppose the stamps were cut off for some stamp-collecting child. But if you have any other correspondence from the beginning of the century you should keep the whole envelope, stamps and all; that’ll make the stamps much more desirable to a philatelist—and be specially careful with blocks of four.

I assume you’re busy clearing out the house—very natural. Congratulations! I’m doing the same and I’ve been gradually learning all kinds of things, one being that if you give special treasures to young people they’re not usually particularly pleased to have them. If you persist, they get more and more polite and more and more irritated. Have you noticed? But, do you know, there’s a flea market every Saturday and Sunday in Sandvikstorg square these days—how about that? Anyone can go there and find what they want for themselves without needing to feel either put upon or grateful. Brilliant idea.

You say you’re gloomy and depressed but that’s normal, Cecilia, nothing to worry about. I’ve read somewhere that it’s a physiological phenomenon, doesn’t that make you feel better? I mean, you feel depressed, so you sit down and think, “Oh well, it doesn’t matter, there’s nothing I can do about it, it’s just the way things are.” Isn’t that the truth?

What else shall I tell you—oh, yes, I’ve got rid of my potted plants and I’m trying to learn a little French. You know, I’ve always admired you; you speak the language so perfectly. What’s that elegant way they have of ending a letter?—Chère madame, I enclose you, no, me, in your—oh you know.

I’m just a beginner.

Chère petite madame, I do miss you sometimes—

Love, Klara

Dear Sven Roger,

So good of you to make sure the porcelain tiled stove’s in working order again. If those officials come back and say it’s against the law to light it I shall speak to my solicitor; the stove’s an article of Historic Importance, as we’re all well aware.

When you come back from your holiday you’ll find that Mrs. Fagerholm from the floor above me has gone in for an unnecessarily sweeping clearance of her attic storage space. She parked her unnameable possessions in front of my own space, so I naturally threw the whole lot out into the corridor.

I remember you once said you’d like some indoor plants for your summer cottage. I’ve put my own collection of potted plants out in the yard next to the garbage cans and anyone’s welcome to take what they want; anything left can go into the trash. I’ll keep them watered for the time being. To explain my apparently heartless behavior, I’d just like to say that these potted plants have weighed on my conscience for far too long; they always get either too little water or too much, one can never get it right.

By the way, don’t hurry to wash the windows; they have what looks like an attractive light mist on them just at the moment; it would be a pity to disturb it. With my very best wishes for your summer holiday,

K. Nygård

P.S. Don’t say anything to the Fagerholm woman. I have to admit I really enjoyed throwing out her rubbish.

Camilla Alleén

“Woman to Woman”

Dear Ms. Alleén,

Thank you for your kind letter. But I do not consider myself to be in a position to take part, as you put it, in an enquiry into the problems and pleasures of old age.

One could of course maintain that, though taking part might be difficult, it could also be interesting—but I don’t see any point in listing one’s obvious misfortunes, while trying to describe what’s interesting about being old seems to me to be a private matter most unsuited to the dogmatic statements demanded by questionnaires.

My dear Ms. Alleén, I’m afraid you’re not very likely to get many honest answers to your questions.

Yours sincerely, Kla

ra Nygård

Translated by Silvester Mazzarella

MY BELOVED UNCLES

HOWEVER tired of each other they must have grown from time to time, there was always great solidarity among Pastor Fredrik Hammarsten’s children—four boys and two girls. The girls married quite young and moved to other countries, far enough away that the others could think of them without concern or annoyance. But Torsten, Einar, Olov, and Harald continued to live in Stockholm, where Grandfather was the preacher at Jakob’s Church. Maybe they knew one another too well to socialize in the usual way, but they couldn’t help being aware of one another’s various activities and sometimes foolish opinions.

Sister Elsa married a priest and moved to Germany, and Mama married a sculptor and went to Finland. She signed her drawings Ham, but Uncle Einar called her Signe.

I knew that when they were young and Uncle Einar’s studies were at their most intense, it was Ham who watched over his work and saw to it that none of his strength or confidence went to waste. She was tireless and ambitious on his behalf.

And then she went away. What a triumph it must have been when she learned that Uncle Einar had been named Professor of Medical Chemistry at the Karolinska Institute! He must have written to tell her, because we had no telephone.

Mama never said a word about being homesick, but as often as she could, she took me out of school and sent me over to her brothers to see what they were up to and to tell them what was happening with us, and the most important part was seeing Uncle Einar and trying to get a sense of how his scientific work was going.

“It’s going all right,” he said. “You can tell Signe that I think it’s moving in the right direction, but very slowly.”

“How so?” I said, sitting at the ready with pen and paper.

Uncle Einar gazed at me for a moment and then said very amiably that cancer was like a string of beads where it’s impossible to remove one of the beads from the others without the whole necklace going to pieces.

Comet in Moominland

Comet in Moominland Moominvalley in November

Moominvalley in November Moominland Midwinter

Moominland Midwinter Moominpappa's Memoirs

Moominpappa's Memoirs Sculptor's Daughter

Sculptor's Daughter The Listener

The Listener Tales From Moominvalley

Tales From Moominvalley Letters from Tove

Letters from Tove The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories Travelling Light

Travelling Light Finn Family Moomintroll

Finn Family Moomintroll Moominsummer Madness

Moominsummer Madness Moominpappa at Sea

Moominpappa at Sea Fair Play

Fair Play Letters From Klara

Letters From Klara Art in Nature

Art in Nature The Moomins and the Great Flood

The Moomins and the Great Flood The Exploits of Moominpappa

The Exploits of Moominpappa The Woman Who Borrowed Memories

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories